When I first learned that a taxi driver from Torquay volunteered to be mummified like an ancient pharaoh, I had to pause and just sit with that thought.

A regular man. A modern hospital. A team of chemists and forensic pathologists. And a three-thousand-year-old recipe that once wrapped kings for eternity. Tomato Plant Basics (Without the Jargon).

For me, this story turns mummification from a museum word into something very human and strangely close. It becomes less about dusty bandages and more about love, memory, science, and the lengths we go to in order to hold on to a face.

In this article, we will walk together through three worlds at once.

- The spiritual world of ancient Egypt, where the body was a passport to the afterlife.

- The scientific world of a modern lab, where every grain of salt and drop of resin is carefully measured.

- And our own world, where one man’s last wish helps us see death, care, and knowledge in a new light.

Why The Egyptians Fought So Hard Against Time

When we stand in front of a mummy in a glass case, it is easy to focus only on the shock factor. Dried skin. Wrapped limbs. A face frozen in place Comanche Attack that Terrified the Spanish.

But for the ancient Egyptians, this was not a horror scene. It was an act of deep care.

They believed that a person was made of many parts. There was the physical body. There was the ka, a kind of life force. There was the ba, often shown as a human-headed bird, that could move between worlds. For all of this to work, the body needed to stay whole and recognizable.

If the body decayed, the path to the afterlife broke.

If the face collapsed, the spirit could lose its anchor.

So mummification was not only a funeral service. It was high-stakes protection. It was a promise from the living to the dead.

Instead of letting the hot desert sun do all the work, specialist embalmers turned preservation into a delicate, step-by-step science. Over centuries, especially in the New Kingdom, around the time of Tutankhamun, they refined those steps with extreme care.

The Golden Age Recipe, In Simple Terms

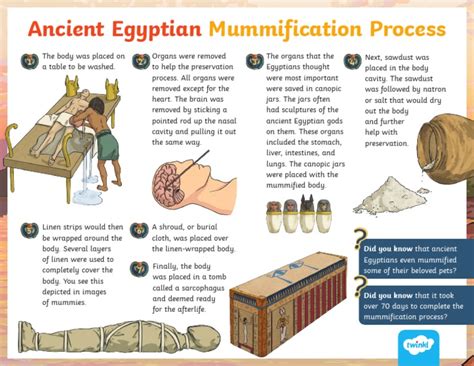

At its heart, Egyptian mummification is a system for stopping rot. The embalmers needed to remove moisture, block bacteria, and seal the body against insects, mold, and time.

The full ritual was packed with prayers and symbols, but underneath the ceremony sat a very practical chemical plan. Let us walk through it in simple language How to Start a Worm Farm.

Step 1: Preparing the body

The body arrived at the embalmer’s workshop. Priests and workers washed it with water and sometimes with palm wine. The alcohol in the wine helped kill germs and start the cleaning process.

Step 2: Removing the internal organs

The soft organs decay first. So the embalmers gently opened the side of the body and removed the liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines. The heart normally stayed. It was seen as the center of thought and emotion.

Those organs did not just get thrown away. They were dried carefully and placed in special containers called canopic jars, each watched over by a protective god.

The brain was removed in a different way. Long metal tools went up through the nose to pull the brain tissue out. To the Egyptians, the brain did not matter much. The heart was what counted.

Step 3: Packing and drying with natron

Now came the most important ingredient of all: natron.

Natron is a naturally occurring mix of salts from dry lake beds in Egypt. It pulls water out of anything it touches. For embalmers, it was like a super-powered drying agent and disinfectant in one.

They packed natron inside the empty body cavity. They laid the body in a bed of natron and covered it completely. For around forty days, sometimes longer, the salt drew out almost every drop of moisture.

What began as a soft, flexible body slowly turned into something firm, dry, and much more stable.

Step 4: Oils, resins, and gentle repair

After the drying period, embalmers brushed off the natron. The body was lighter and stiff, but still recognizable.

Now they treated the skin and the inside of the body with oils and resins. Many of these came from tree sap. Some were imported from faraway lands. Modern tests show that these resins have strong anti-bacterial and anti-fungal powers. They also give off a sweet, Sponge Gourd Luffa smoky scent.

The embalmers used them like a mix of medicine and sacred perfume. They slowed decay even more, sealed small gaps, and prepared the body for the long sleep.

If needed, the team also added linen pads or packing material to keep the face and limbs shaped. They did cosmetic repairs with great care, not for vanity, but to protect identity.

Step 5: Wrapping the body like a promise

Finally came the famous bandages.

The embalmers wrapped the body in many layers of linen. Between some layers they tucked amulets for protection. They painted or resined the outer layers to create a rigid shell.

Every turn of the cloth, every knot, matched a line of ritual speech. It was like a long conversation between the living and the dead.

At the end, the person was no longer just a body. They were a mummy, ready to meet Osiris and move into a new life.

Enter Alan Billis, A Modern “Pharaoh”

Jump forward more than three thousand years.

A taxi driver in Torquay, England, named Alan Billis, learns he has terminal lung cancer. He reads about a team of scientists who want to recreate Egyptian mummification as faithfully as they can. They are looking for someone willing to donate their body after death for the experiment.

Alan signs up. His wife and family, after the first surprise, give their blessing. He jokes about it. He knows his story will help science and education. He knows his grandchildren will remember him not only as Grandad, but also as “the modern mummy.”

After Alan’s death, his body is taken to a forensic pathology lab in Sheffield Eisenia fetida Red Wiggler Guide. A team led by chemist Dr. Stephen Buckley and a forensic pathologist set out to follow the ancient playbook. The documentary that follows this work, Mummifying Alan: Egypt’s Last Secret, later wins major awards and captures the attention of viewers around the world.

Instead of a temple workshop by the Nile, we see stainless steel tables, bright lights, and masked staff. Yet the goal is the same. Keep a human body intact against the pull of time.

Rebuilding A Lost Technique, One Grain At A Time

What moves me most about this project is how carefully the team tried to respect both Alan and the ancient embalmers.

They did not simply “wing it” with salt and bandages. They spent years studying real mummies, chemical residues, and historical records. They examined traces of oils, resins, and waxes on ancient wrappings. They looked at how natron behaves in different forms. They tested mixtures on animal tissue before ever touching a human donor.

Then they brought all of that patient work into the lab.

Step by step with Alan

The team followed the classic stages.

- Alan’s body was washed and prepared.

- The internal organs were removed, treated, and stored, just as the Egyptians had done.

- His body cavity was cleaned and packed.

- He was immersed and covered in natron to dry completely. Reports describe him staying in this salty “bath” for around a month or more, similar to ancient timelines.

After the drying, the scientists inspected his tissues. The skin had tightened and darkened. The body had lost a large portion of its original weight due to water loss.

They then applied oils and resins, again based on ancient recipes. Many of these substances have names that sound exotic and far away, but their role is simple. They harden, seal, and protect. They also likely carried strong symbolic meaning for the original embalmers.

Finally, Alan was wrapped in linen. The team used bandaging techniques copied from New Kingdom mummies, especially those from the same dynasty as Tutankhamun.

The Moment The Bandages Came Off

After some months, the team needed to check how well the process worked Rhaphidophora decursiva Dragon Tail. A group gathered as the outer layers of bandage were carefully opened.

The face that emerged was not the face of a fresh, living man. It was dry, dark, and still. But it was clearly Alan. The nose, the mouth, the overall shape of his features were preserved in a way that felt shockingly familiar. Observers describe a strong mix of awe and relief in the room.

For the scientists, this was proof that their reconstruction of the ancient method was on the right track. For Alan’s family, it was confirmation that his unusual wish had become a real and respectful act.

For those of us watching from the outside, it raised a deeper feeling. We could see, in real time, how human skill and care can push back against decay, even if not forever.

What We Learn When We Look Under The Bandages

This one experiment does not answer every question about mummification. Ancient Egypt lasted for millennia. Techniques changed by period, region, wealth, and personal taste.

Still, the work with Alan and other recent studies give us powerful new insights.

Ancient embalmers were serious chemists

For a long time, people spoke about mummification as if it were mainly religious ritual. The prayers, the gods, the symbols on the sarcophagus all took center stage.

Now, thanks to modern chemical analysis, we see just how advanced the practical side also was. Scientists have identified complex mixes of plant oils, resins, and even imported ingredients like conifer resins and bitumen in some mummies. These compounds fight bacteria and fungi and help create a tough, water-resistant coating on skin and bandages.

In other words, Egyptian embalmers were early masters of materials science Vanilla planifolia Albo-Variegata. They built anti-microbial armor using what they had around them and what traders could bring along ancient routes.

Natron is more than “just salt”

Many school books simplify natron as ordinary salt. In reality, it is a special natural blend that includes sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium chloride, and sodium sulfate. This mix pulls water from tissue more effectively than table salt alone and helps create a harsh environment for microbes.

The experiment with Alan confirms how strongly natron can dry and stabilize a human body when used in bulk and over time.

Preservation is physical, emotional, and cultural

When we think of mummies as museum items, we risk losing the emotional side. But the story of Alan brings that feeling back.

His wife could say, with a strange kind of pride, that she was married to a mummy. His grandchildren could point to a documentary and, one day, to a specimen in a teaching collection and say, “That is our grandad, helping people learn.”

Likewise, ancient families would have stood in tombs, looking at the wrapped forms of people they loved. Those bodies were not experiments for them. They were treasured anchors in a world filled with change and uncertainty.

How This Story Changes The Way We See Death

Instead of seeing mummification as something remote and almost cartoonish, the journey of Alan Billis pulls it into everyday life.

We see a man who drove people to work, to the grocery store, to the doctor. We see a family that laughed at his jokes and rolled their eyes at his big ideas. We see scientists who cared not only about data, but also about dignity.

When all of that is set beside the deep beliefs of ancient Egypt, something powerful happens. The line between “them” and “us” grows thinner.

- They wanted to hold on to the memory of a face. So do we.

- They used the best science they knew to protect a body. We do the same, in hospitals, in labs, and in funeral homes.

- They built rituals to show respect for the dead. We gather, speak, sing, and tell stories for the same reason.

After more than three thousand years, the tools look different. The core feelings do not.

What This Means For Science And For Us

Projects like the mummification of Alan Billis sit at a unique crossroads. They are part chemistry experiment, part history lesson, and part human story.

For science, they offer clear benefits.

- They help test theories about how ancient techniques worked in real life.

- They show how certain materials behave over months and years, not just in short lab trials.

- They reveal how carefully ancient craftspeople paid attention to detail, from temperatures to drying times to the layering of cloth.

For education, they give museums and teachers a powerful, modern example to share. Students can connect more easily to a story about a taxi driver and a documentary than to a distant pharaoh alone.

For all of us on a personal level, they invite honest reflection.

Death can feel abstract until we see a body treated with such precise care. Then it becomes real, but in a way that is not only frightening. It can also feel peaceful. The work is slow. The hands are gentle. The goal is protection, not display.

When we look at it that way, mummification is not only an ancient curiosity. It is one more way humans have tried to say, “You mattered. You still matter. We will not let time erase you easily.”

Echoes From A Salt-White Table

In my mind, I often picture two rooms.

In one room, thousands of years ago, a small group of embalmers bend over a body by the Nile. Oil lamps flicker. They move with practiced hands. Every step matches a ritual they learned from teachers who learned from teachers before them.

In the other room, in modern England, bright lamps glare off metal and glass. Machines beep softly. A chemist, a pathologist, and their team stand over Alan’s body. They consult notes, adjust natron levels, and discuss resin blends.

Between those two rooms lies a long river of time. But the work, the focus, and the respect form a bridge across it.

When we stand in front of a mummy now, whether it is a long-dead pharaoh or a man named Alan who drove a taxi, we are not only looking at death. We are looking at human determination to understand the world, to hold on to identity, and to make love and memory stronger than decay.

That, to me, is the real secret of Egypt’s “golden age” and of the modern lab that tried to follow in its footsteps. It is less about magic and more about care, patience, and the quiet courage to face death with open eyes and steady hands.